Hack for your future

Sarah Gold was chosen as one of our Future Pioneers in 2014, thanks to her innovative creation The Alternet, a reimagined internet with user privacy at its heart. Here she asks for the all too loaded term ‘hacking’ to be reconsidered and argues that hacking is, in fact, often at the core of progress.

Built-in obsolescence is irritating. I currently own a phone that looks brand new, but I cannot use it because of failure of one component: its battery. I feel disempowered and very frustrated; it’s unfair that I should have to invest in a totally new product when all I need is an upgrade for one part. Hacking is the answer.

Connected hardware has been so completely co-opted by the data capitalist companies that hacking is often considered wrong. Hacking has become a loaded term - simultaneously an activity conducted by cyber criminals, a collaborative computer programming event and a do-it-yourself enthusiast’s dream. Whilst our black-boxed products and media scare stories continue to give hacking a bad name, we must remember that the web and all other forms of technological wonder were made from some form of hacking. Hacking is both a form of tinkering and user-centred design; rethinking, changing and making improved software or hardware. And it is not necessarily illegal.

Hacking is fundamental, and the ability to understand and adapt objects around us is critical. To modify or customise everyday products in order to repurpose or improve them is a basic form of invention. In fact the Royal Institute’s 2014 Christmas Lectures were themed ‘How To Hack Your Home.’ The lectures encourage its young audience to tinker around their own homes, to not accept the status quo of homeware but interrogate it. The lectures are one example of a growing movement of do-it-yourself, user-centred innovation being accelerated by the growth of ‘smart’: smart cities, smart homes, smart fridges…In fact by 2050, IBM predict that over 10 billion objects will be internet-connected and ‘smart’. But how can we call this trend ‘smart’ if its focus is the technology rather than people?

In response, a slowly-growing number of companies are delivering devices and systems that are open to user-led innovation - where individuals are empowered to make something themselves, rather than relying on manufacturers to act as their agent. These companies deliberately design open standards into their products so hobbyists can become inventors - plugging their own designs into the framework. For instance, the open hardware company littleBits recently launched their Smart Home Kit comprising snap-together electronics that give homeowners the ability to make, programme and test their own home automation products. Customers are encouraged to make and launch their own Bits that, if successful, will be manufactured by littleBits and sold for profit. Or consider Project Ara, Google’s modular phone, that allows anyone to design custom modules to plug into the phone. In this way innovation can come from the edge, establishing a more vibrant and varied development lab than would be possible in-house alone.

The do-it-yourself shift is intrinsically linked to the emerging third industrial revolution and the democratisation of production. Machines like 3D printers and CNC routers are transferring the power of production to the economic ‘long tail’ - to everyone. In doing so, these tools are changing not only what is being produced, but who is capable of producing.

This open design movement is made possible by the dissemination of knowledge over the web, shared under a variety of copyleft and Creative Commons licences. These licences are increasing the volume of cultural, educational and scientific content available ‘in commons’ - available and freely accessible for everyone to use, ‘hack’ or adapt and remix. By openly sharing knowledge, designs can spread far more quickly and widely than ever before, providing the tools and inspiration for anyone to become an inventor, and make something extraordinary.

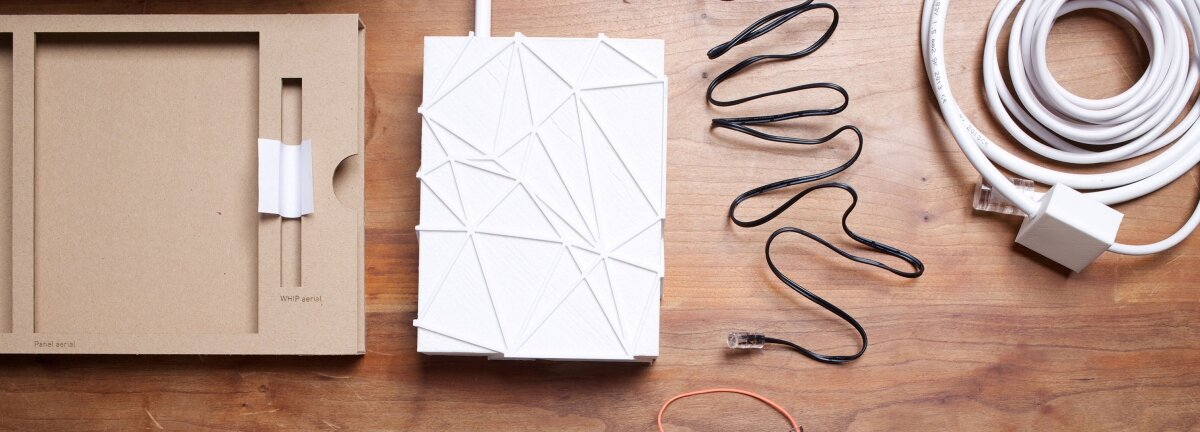

Alternet data licenses and 3D printed hardware

Alternet data licences based on the Creative Commons licences.

Alternet kit instructions.

3D printed Alternet hardware.

This idea of consumer empowerment drove my masters’ degree project, The Alternet - a proposal for a civic network where individuals own their own data through data licences. The project imagined a future of hardware that is transparent, modular and shape agnostic. The Alternet’s hardware is made by 3D desktop printers, establishing an open derivative market for Alternet products and the opportunity for homeowners to co-create their own hardware. Alternet routers disappear seamlessly into living rooms, printed as a piece of cornicing or other detail. Tools that provide consumer empowerment, transparency and hackability are crucial, because they allow us to see past the linear present of predefined, closed ‘smart’ products and systems, to a future path of plurality, choice and innovation.

But for now, until these tools become commonplace, I guess I will have to make do with an external battery pack to recharge my phone.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Want to keep up with the latest from the Design Council?