Can creativity and imagination overcome the engineering skills gap?

Dr Andy Bell is a researcher in the Design and Prototyping Group, which is part of the University of Sheffield’s Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre (AMRC) with Boeing. The AMRC is one of seven established manufacturing and process research centres which make up the High Value Manufacturing Catapult consortium. Here, Andy talks about the perceived skills gap in the manufacturing sector.

I have a confession to make - I’m a designer. I carry a sketchbook with me most places I go and have a bookshelf that covers topics ranging from interior design, to furniture, architecture, Bailey bridge and supersonic aircraft design. Why? Because the process of design fascinates and frustrates me in equal measure.

My first formal encounter with design was a split-second decision in 2001 to go back to university and study engineering design. I have worked in development roles ever since and passed through several of the proposed doomsday events, where the skills gap was supposed to finally engulf the entirety of British high value manufacturing.

My current role, within the Design and Prototype Testing Centre of the University of Sheffield’s Advanced Research Manufacturing Centre (AMRC) with Boeing, is forcing me to rethink the whole idea of a skills gap - and what it means for the UK economy.

Design is an activity that uncovers and realises the expectations of the user - design for high value manufacturing is no different. During that activity organisations have to not only determine where their high value offering lies, but also to design their products to meet that offering. So, is there a skills gap in UK design capability in the high value manufacturing sector?

Well, ‘yes and no’ is the real answer. The skill set of the team I work with here is unparalleled, with individuals capable of doing things with computer aided design (CAD) and analysis software that, frankly, I wouldn’t even know how to describe. These are young people, with an average age somewhere around thirty, so there is no lack of talent coming through the ranks.

I’m a big advocate of early, low-cost physical prototyping.

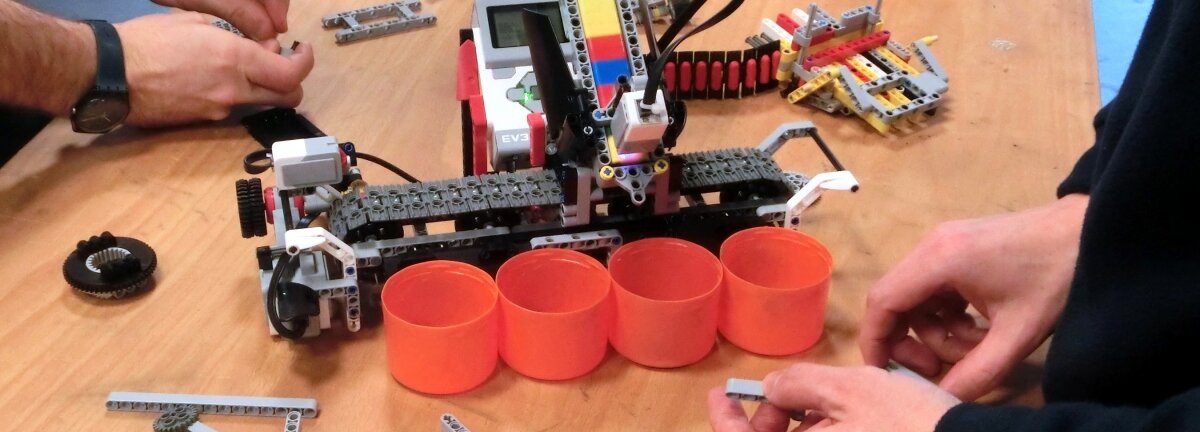

Where we have struggled in the past, and where I believe other organisations also find difficulty, is in aspects of imagination. Too often an engineer will rely on CAD or analysis software to answer a question and find themselves stuck in a loop. There is a reluctance to produce a low-fidelity prototype by sticking bits of cardboard and plastic together to quickly test an idea in engineering design, although this is a common practice for the industrial or product designer.

We demonstrated this approach in the development of our 3D-printed UAV, where several of the design issues were resolved by making a physical, low-fidelity prototype and trying it in the field. The missing skill in many cases is the lack of an awareness of other processes which can help. So what is the answer?

Creativity and imagination, they can both be taught - I do this on a regular basis with teams from across the high value manufacturing sector with good results. Model making skills are easy to learn, but you can now also pick up a 3D printer for a few hundred pounds for model-making.

I’m a big advocate of early, low-cost physical prototyping, it helps more than most people realise and can uncover things that the screen simply doesn’t show. Otherwise, get yourself a good sketchbook, a mechanical pencil and a decent bookshelf, draw, write and read.

Skills gap, what skills gap?

Subscribe to our newsletter

Want to keep up with the latest from the Design Council?